Atlantic hurricane- As summer in the Northern Hemisphere approaches, forecasters begin watching every bout of rainy weather between the Gulf of Mexico and Africa. Each counterclockwise swirl of wind or burst of puffy clouds there has the potential to organize into a life-threatening tropical storm.

Atlantic hurricane

About half of the tropical storms that formed over the past two decades grew into hurricanes, and about half of those became the monsters of coastal destruction we call major hurricanes. We’re now accustomed to seeing about 16 tropical storms per year, though that number can vary quite a bit year to year.

What are the warning signs that we might be in for another record hurricane season like 2020, when 30 tropical storms formed, or a quieter one like 2014, with just eight?

Atlantic hurricane- The National Hurricane Center issued its first seasonal forecast of 2021 on May 20, and it expects a more active than normal season, with 13 to 20 named storms, six to 10 hurricanes and three to five major hurricanes.

Where tropical storms begin

Hurricanes live in the atmosphere, but they are fed by the ocean. First, let’s look even farther upstream and find out where they come from.

Like growing crops, hurricanes will be plentiful and robust with a large number of seeds and favorable environmental conditions.

The seeds of tropical storms are small and hardly menacing weather disturbances. You’ll find them scattered throughout the tropics on any given day. In the Atlantic, some start as clusters of thunderstorms over Africa, or as clouds near the Cape Verde Islands off Africa’s west coast.

The vast majority of these seeds do not survive beyond a few days, but some are swept up by the easterly airflow to be planted over the tropical Atlantic Ocean between about 10 to 20 degrees north latitude. This is the field where growth is really fueled by the ocean. From there, developing tropical storms are carried westward and northward by the “steering currents” of the atmosphere – avoiding the equator where the crucial effect of Earth’s rotation is too small for them to develop further.

The more seeds, the better chance of an active hurricane season.

Several factors influence the level of tropical storm seeding in a given year, but forecasters’ eyes are usually trained on the African monsoon in the spring.

Once those seeds emerge from the African coastline or from pockets of warm, rising air popping up elsewhere over the ocean, attention shifts to the environmental conditions that can fuel or limit their growth into tropical storms and hurricanes.

Warm water fuels hurricanes

In general, tropical storms thrive where the surface ocean is a balmy 80 F (26.7 C) or warmer. That’s why hurricanes are rare before June 1 and are most likely to occur August through October, when the ocean is at its warmest.

The main fuel supply for tropical storms is the heat energy in the upper ocean, the top 100 feet (30 meters) or so.

It’s more than just the temperature of the surface, though. A major factor in the development of very strong hurricanes is how deep the warm waters extend, and how sharply separated the warm layer is from the cold waters below. This is because hurricanes churn up the ocean as they move along.

If the layer of warm water is shallow and easily mixed, it doesn’t take much churning to dilute the heat energy at the surface with cold water from below, leaving less energy for the hurricane. But if the warm water goes deeper, the storms have more fuel to draw from.

(Edited from NOAA and the Conversation)

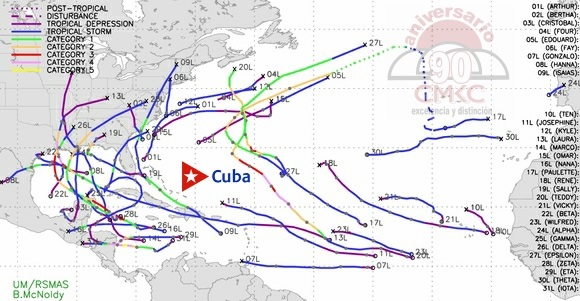

A Very Active 2020 Hurricane Season

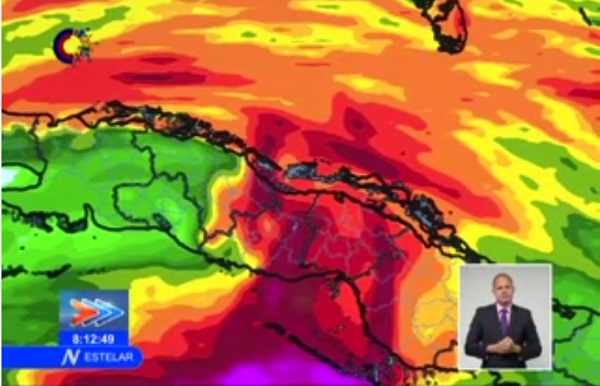

The hurricane season of 2020 was a very busy one: twenty-nine tropical storms and one subtropical storm originated in the North Atlantic. The first one (Arthur) was in mid-May, and the last one (Iota), on November 13.

The number of cyclones observed greatly exceeds the average for the period 1981-2010 (twelve) and exceeds by two the number recorded in 2005.

Thirteen storms turned into hurricanes; of these, six were high intensity, i.e., category 3, 4 or 5. The most intense hurricane was Iota (which evolved in the Caribbean Sea), with a minimum central pressure of 917 hPa and maximum sustained surface winds of 260 km/h, (161 m/h).

September was the busiest month, with ten systems (new record) named: Nana, Omar, Paulette, Rene, Sally, Teddy, Vicky, Wilfred, Alpha and Beta.

Incredibly, twelve storms reached the continental United States (record); six of them hit as hurricanes. Five storms made hit the state of Louisiana (record); Laura was the most powerful.

In October, Gamma, Delta and Zeta hit the Yucatan Peninsula, and in November, Category 4 hurricanes Eta and Iota caused major disaster in Nicaragua and other Central American territories.

Only two tropical cyclones moved over the Cuban archipelago: Laura in August and Eta in November. Both weather systems caused heavy rains, tropical storm winds and strong swells.

Iota, the most intense tropical cyclone of the season. Image: Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies.

Impact of tropical storm Laura across the country

Weathering the storms of the 21st century