Translater: Guillermo Rodriguez Cortes

At the beginning of 1895, the atmosphere in Cuba was frankly insurrectionary. The failure of the Fernandina Plan, when the U.S. authorities seized the arms of the expedition organized by Jose Marti to restart the Necessary War, far from discouraging the independence fighters, raised the revolutionary spirit.

The chiefs inside the Island, anxious to return to the fight in the countryside, urged the Apostle to sign the order of the uprising with the argument that the colonial Government was already on notice and at any moment they could be arrested.

On January 29, Marti summoned Mayia Rodríguez, to whom Maximo Gomez had delegated his «express authority and power», and Enrique Collazo, who vouched for his authority, to evaluate the news and reports received from Cuba. Those gathered agreed on the need to issue the order for the uprising as soon as possible, which was written by Marti and signed by the three of them. In it, the simultaneous uprising was authorized, or with the greatest possible simultaneity, of the regions involved during the second half of February, but not before.

This decision was sent to the Cuban Juan Gualberto Gomez and in to all the groups of the West, with copies to Guillermon Moncada, in Santiago de Cuba; Bartolome Maso, in Manzanillo; Francisco Carrillo, in Remedios and to Salvador Cisneros Betancourt in Camaguey. The documents were carried to Havana by Juan de Dios Barrios.

In the first days of February 1895, in his condition of Delegate of the Revolutionary Party (PRC) in Cuba, Juan Gualberto received the already mentioned order of uprising and «others that he had to direct», according to his testimony. The young student Tranquilino Latapier left for [Oriente] to meet with Moncada, with the precise warning that only after obtaining the agreement of the general from Santiago, he could go to Manzanillo to see Maso. He succeeded and returned to the capital with the acceptance of the two eastern chiefs and an interesting proposal from Quintin Bandera: to set February 24th, the first Sunday of Carnival, as the date of the uprising.

Pedro Betancourt, a doctor from Matanzas, went to Las Villas to deliver Marti’s instructions to Francisco Carrillo. The latter refused to second the simultaneous uprising due to the shortage of weapons. But when informing Juan Gualberto by telegram, Betancourt wrote: «Carrillo well», which the Delegate of the PRC in Cuba interpreted as the mambi from Las Villas had accepted the date of the uprising. Camagüey, meanwhile, reiterated that it would not rise immediately. Neither in the order of uprising nor in the later document written by Marti or Juan Gualberto there is a place distinguished as the main center of the uprising. The plan always was for a simultaneous insurrection.

In Cuba there were 35 cries at the same time as Baire in 1895.

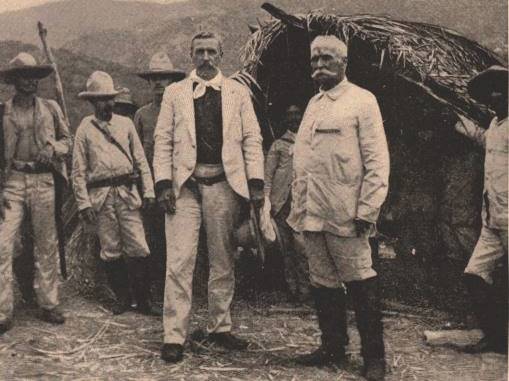

Days before the fixed date, the eastern mambi chiefs had abandoned their houses so as not to be located by the colonial authorities. Guillermon, for example, mounted on a mule, evaded the Spanish vigilance and went to the town of Auras where he stayed at the house of a patriot. On the morning of February 24, he left his refuge and with a group of patriots, camped in the Loma de La Lombriz, Alto Songo.

In his farm Colmenar de Bayate, near Manzanillo, at dawn, Bartolomé Masó raised the flag of the lone star and established a mambi camp there. Eighty insurrectionists rose up in Yara and entered the town brandishing their machetes; there they collected weapons. Near Bayamo, Joaquin Estrada Castillo rose up in his farm El Mogote; Esteban Tamayo, in Vega de la Piña with 80 comrades; Jose Manuel Capote, in San Diego, with 40 armed men.

Periquito Perez had precise instructions from Antonio Maceo to control with his people the south coast of the jurisdiction of Guantanamo, for the expeditions that were to disembark there. He had been hiding since October 1894 due to the persecution by the Spanish authorities, and then he received orders from Guillermon Moncada to set Guantanamo ready for war.

The Cry of Baire for the Freedom of Cuba (Part II)

Translater: Guillermo Rodriguez Cortes

At noon, Victoriano Garzón left Santiago with a group of independence fighters and set up camp near the city, in the San Esteban farm; Alfonso Goulet, also following Guillermon’s orders, revolted in the town of El Cobre; Quintín Bandera, at the head of a handful of patriots, all armed, camped near San Luis; Silvestre Ferrer set fire with his men to the town of Loma del Gato, traditional center of operations of the Spanish Army and, in Palma Soriano, Cubans of different generations joined him.

Days before the date set for the uprising, Saturnino Lora had received the following message: «…By order of General Moncada, to rise on the 24th in the afternoon and await orders…»

Guillermon also instructed him to warn Fernando Cutiño Zamora and the patriots of Jiguaní. Lora complied fully. In the afternoon he gathered his comrades at the Puente de la Herrería and in front of them he marched towards the Baire square, where he proclaimed himself in rebellion.

He took out his revolver and fired his six shots into the air. Cutiño, José Reyes Arencibia, and a reduced group entered Jiguaní almost at nightfall. They remained here until about nine o’clock at night and left for Baire. Both detachments marched together towards La Salada, to place themselves under the command of Jesus Rabí (February 27).

Baire People’s Council, a Landmark in History

In the West, a small group that included Juan Gualberto Gómez and Antonio Lopez Coloma met in the vicinity of the town of Matanzas de Ibarra.

This uprising was to be led by General Julio Sanguily, whose controversial attitude today raises many suspicions among historians and some even label him as a traitor to the homeland. Inexplicably, this high-ranking mambi officer allowed himself to be arrested in Havana by the Spanish authorities on the morning of the 24th.

In the meantime, Ibarra’s patriots without scouts or military chief were easy prey for the Spanish troops and many of them fell prisoner. Lopez Colonia was shot by the colonialists. The uprisings of Jagüey Grande and Aguada de Pasajeros met the same fate as that of Ibarra’s.

Having been granted a pardon by the Spanish Government, most of the conspirators went abroad, but later, by different means, they returned to the fight to join the Liberation Army. According to several sources, some 35 localities in different parts of the country rose up in arms against Spanish colonialism on that February 24th. Only in the eastern region, especially in the southern part of the country, the guerrilla groups were able to consolidate.

The Cry of Baire for the Freedom of Cuba (Part III)

Why Baire

There are different theories about it. In the first place, the media propaganda of Spanish colonialism overestimated the uprising in that locality to falsely attribute to it an autonomist character, with the mischievous purpose of misleading Cubans.

In several national congresses of History, celebrated throughout the 20th century in Cuba, Emilio Roig de Leuchsenring fought against the erroneous tendency to center in Baire the beginning of the War of 95.

Two other distinguished specialists, Fernando Portuondo and Hortensia Pichardo, also stood against that historical simplification, which attracted the animosity of certain narrow minds, afflicted with an absurd regionalism, that have not hesitated to appeal to apocryphal paragraphs like the one found in the National Archive (Jose Marti. Fondo Donativo. box 632, number 50) and that the Center for Marti Studies does not include in the Complete Works of the Apostle because there are great doubts about its authenticity.