Translater: Guillermo Rodriguez Cortes

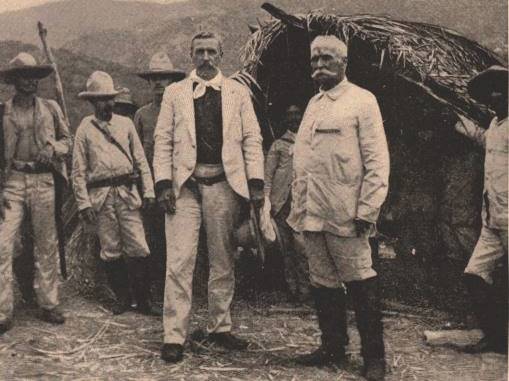

At noon, Victoriano Garzón left Santiago with a group of independence fighters and set up camp near the city, in the San Esteban farm; Alfonso Goulet, also following Guillermon’s orders, revolted in the town of El Cobre; Quintín Bandera, at the head of a handful of patriots, all armed, camped near San Luis; Silvestre Ferrer set fire with his men to the town of Loma del Gato, traditional center of operations of the Spanish Army and, in Palma Soriano, Cubans of different generations joined him.

Days before the date set for the uprising, Saturnino Lora had received the following message: «…By order of General Moncada, to rise on the 24th in the afternoon and await orders…»

Guillermon also instructed him to warn Fernando Cutiño Zamora and the patriots of Jiguaní. Lora complied fully. In the afternoon he gathered his comrades at the Puente de la Herrería and in front of them he marched towards the Baire square, where he proclaimed himself in rebellion.

He took out his revolver and fired his six shots into the air. Cutiño, José Reyes Arencibia, and a reduced group entered Jiguaní almost at nightfall. They remained here until about nine o’clock at night and left for Baire. Both detachments marched together towards La Salada, to place themselves under the command of Jesus Rabí (February 27).

Baire People’s Council, a Landmark in History

In the West, a small group that included Juan Gualberto Gómez and Antonio Lopez Coloma met in the vicinity of the town of Matanzas de Ibarra.

This uprising was to be led by General Julio Sanguily, whose controversial attitude today raises many suspicions among historians and some even label him as a traitor to the homeland. Inexplicably, this high-ranking mambi officer allowed himself to be arrested in Havana by the Spanish authorities on the morning of the 24th.

In the meantime, Ibarra’s patriots without scouts or military chief were easy prey for the Spanish troops and many of them fell prisoner. Lopez Colonia was shot by the colonialists. The uprisings of Jagüey Grande and Aguada de Pasajeros met the same fate as that of Ibarra’s.

Having been granted a pardon by the Spanish Government, most of the conspirators went abroad, but later, by different means, they returned to the fight to join the Liberation Army. According to several sources, some 35 localities in different parts of the country rose up in arms against Spanish colonialism on that February 24th. Only in the eastern region, especially in the southern part of the country, the guerrilla groups were able to consolidate.

The Cry of Baire for the Freedom of Cuba (Part III)

Why Baire

There are different theories about it. In the first place, the media propaganda of Spanish colonialism overestimated the uprising in that locality to falsely attribute to it an autonomist character, with the mischievous purpose of misleading Cubans.

In several national congresses of History, celebrated throughout the 20th century in Cuba, Emilio Roig de Leuchsenring fought against the erroneous tendency to center in Baire the beginning of the War of 95.

Two other distinguished specialists, Fernando Portuondo and Hortensia Pichardo, also stood against that historical simplification, which attracted the animosity of certain narrow minds, afflicted with an absurd regionalism, that have not hesitated to appeal to apocryphal paragraphs like the one found in the National Archive (Jose Marti. Fondo Donativo. box 632, number 50) and that the Center for Marti Studies does not include in the Complete Works of the Apostle because there are great doubts about its authenticity.

The Cry of Baire for the Freedom of Cuba (Part II)