Talha Burki

Cuba’s long-standing commitment to health has led to a successful COVID-19 pandemic response, but it is threatened by financial and supplier issues. Talha Burki reports.

As The Lancet Infectious Diseases went to press, Cuba was due to launch a phase 3 trial of its subunit conjugate vaccine against COVID-19. Soberana-2 is one of four candidate COVID-19 vaccines in development in Cuba. It is produced by the Finlay Institute in Havana. On the basis of as-yet-unpublished results from early-stage clinical trials, Vicente Verez-Bencomo, director-general of the Finlay Institute, expects the vaccine to show an efficacy in the region of 80–95%. “We are very optimistic”, he said. If everything goes according to plan, Cuba could start a mass vaccination programme for its 11·2 million citizens sometime in the summer.

• View related content for this articleAfter keeping SARS-CoV-2 at bay for most of 2020, Cuba has experienced a surge of infections in 2021. As of March 8, the country had reported 55 693 cases of COVID-19 and 348 deaths. 23 093 new cases occurred in February alone, almost twice as many as occurred in the whole of 2020. Cuba is still doing far better than the majority of other countries in the region, but a vaccine is urgently needed.

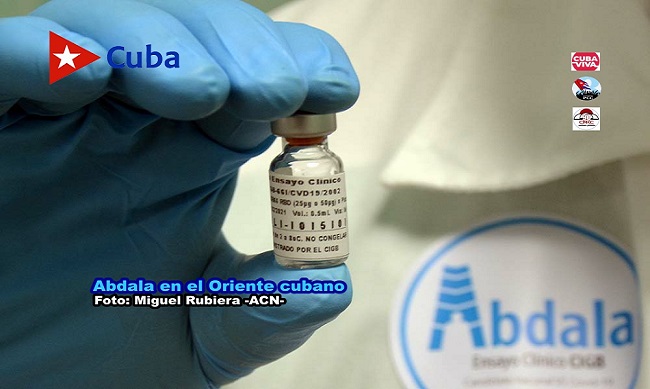

A second phase 3 trial of Soberana-2 is planned for Iran, as part of a partnership between the Finlay Institute and the Pasteur Institute of Iran. A phase 2/3 trial has been scheduled for Soberana-1, which was also developed by the Finlay Institute. The Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (Havana, Cuba) is behind the other vaccine candidates. Abdala and Mambisa, a nasal spray, both entered phase 1/2 trials late last year.

Soberana means sovereign in Spanish. Abdala is the title of a poem by a Cuban revolutionary, and Mambisa is named after the guerrillas who fought against the Spanish colonialists in the 19th century. All of which indicates that the vaccine drive is a matter of national pride. President Miguel Díaz-Canel has visited the Finlay Institute three times over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic. At home and abroad, post-revolutionary Cuban identity has always been bound up with health. In 1960, Cuba joined the relief effort after the Chilean earthquake. In 1963, it sent health-care workers to assist the newly independent state of Algeria.

Cuba’s Henry Reeve Brigade was established in 2005. It has despatched cadres of health-care professionals all over the world to combat disasters and epidemics. Cuban doctors were on the scene in Haiti during the cholera outbreak that followed the 2010 earthquake; they arrived in west Africa during the 2013–16 Ebola crisis. And when COVID-19 spread to Europe, two Henry Reeve teams landed in Italy. By the end of April, 2020, more than 1000 Cuban health-care workers were helping foreign countries respond to COVID-19.

“The international health programme is about solidarity; Cuba believes that healthy populations are the bedrock of global society and they want to support that any way they can”, said Clare Wenham, assistant professor of global health policy at the London School of Economics and Political Science (London, UK). Malaria, polio, tetanus, and measles have been eradicated in Cuba. The island’s successful response to COVID-19 was largely a result of years of investment in primary care and assiduous attention to population health. The country has comprehensive universal health care and one of the highest doctor to patient ratios in the world.

Doctor and nurse teams are embedded in the local community. “Everyone has a yearly routine check-up, and if you do not go, the doctor will come and find you”, Wenham told The Lancet Infectious Diseases. “It means physicians proactively identify problems; there is a real emphasis on prevention.” Disease outbreaks can be detected more or less immediately. Under a model known as CARE, patients are stratified into four categories: apparently healthy, at risk of disease, unwell, and in rehabilitation or recovery. Those at risk of disease include individuals who are overweight, have diabetes, or hypertension. When Cuba registered its first case of COVID-19 on March 11, 2020, it already knew the whereabouts of its most vulnerable citizens.

In an interview with MEDICC Review, family physician Marta Gálvez outlined the advantages of the Cuban system: “The first thing any self-respecting doctor must know is the health situation of the population she serves”, she explained. “The main goal of a primary care physician is health promotion and prevention of diseases, so you have to know your community to design a strategy that suits their needs. CARE is a vital tool: it’s why I know that I have 658 older adults in a total population of 1093 people, and 42 of the elderly live alone.” Roughly one in five Cubans are over the age of 60 years.

“The public health network is very strong in Cuba, but it comes at the cost of civil liberties”, said Wenham. “Cuba is a very specific context; not many countries are going to accept that kind of close medical surveillance, and most governments do not have such tight control over their citizens.” After SARS-CoV-2 entered the island, more than 28 000 medical students led an active screening programme that within a few weeks had reached 9 million Cubans. Cuba had started preparing well in advance of its first case of COVID-19. It quickly shut its borders and set up isolation centres and an efficient system of test-and-trace. But soon after Cuba opened up late last year, cases began to rise.

The pandemic has been extremely expensive. Gross domestic product shrunk by 11% in 2020. Instead of the usual 4 million tourists, Cuba played host to just 80 000. The long-standing economic blockade imposed by the USA has taken a heavy toll. “Health centres and clinics face regular stock outs of basic drugs, such as paracetamol, and other equipment such as bandages”, notes Fiona Samuels, senior research fellow and honorary associate professor at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (London, UK). “The staff are very well trained, but the health infrastructure is decayed and they often lack the basics to allow them to do their work effectively.”

Cuba’s biotechnology industry sprang up in response to the US blockade. It consists of more than 30 research institutions and manufacturers, under the aegis of the state-run conglomerate BioCubaFarma. In the late 1980s, Cuba developed the world’s first meningococcal B vaccine. It produces eight of the ten routinely used vaccines in the country, and sends hundreds of millions of doses abroad. But obtaining raw materials is a constant struggle, especially in the aftermath of the hardening of the American sanctions during Donald Trump’s presidency. “You have situations where suppliers of important components for our industry for several decades have been obliged to suddenly stop; it makes everything more expensive and complicated, and it is real concern”, said Verez-Bencomo. Tourism brings in a flow of much-needed currency, especially since Cuban-Americans have been barred from sending remittances, but with the tourists comes the virus. The Cuban Government reckons that more than 70% of current cases of COVID-19 are linked to new arrivals in the country.

If Soberana-2 proves successful, Cuba plans to export it at low cost after the national vaccination efforts have finished. The centralised health-care system means the domestic rollout is unlikely to be problematic, although pockets of the island are tricky to access. Verez-Bencomo reckons that by the end of the summer the country will have the capacity to produce 10 million doses of vaccine per month. Cubans are excited about the endeavour. “When we call for volunteers for clinical trials, we always have two or three times as many people as we need coming forward”, said Verez-Bencomo. “On the street, everywhere I go, everyone is asking about the vaccine.”